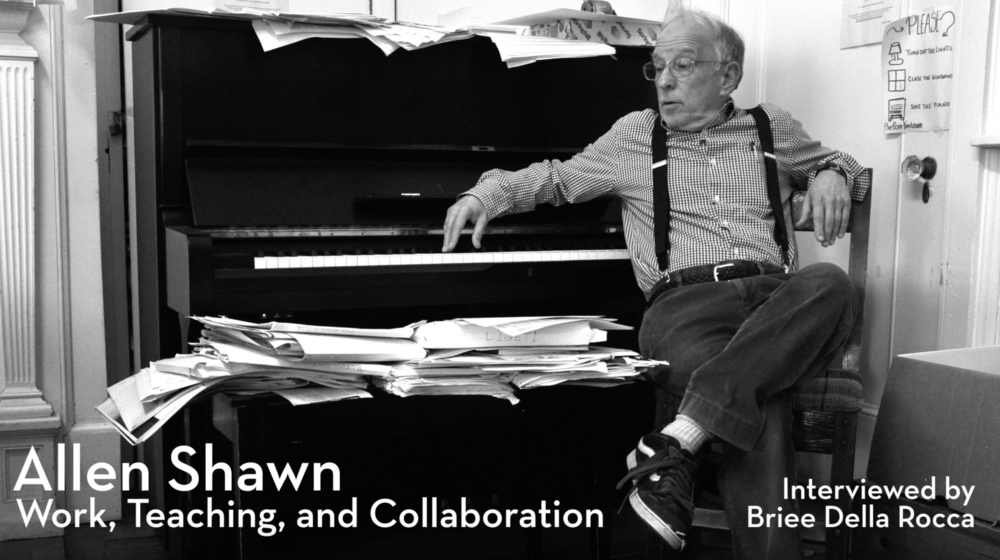

A Conversation with Allen Shawn

Music faculty member Allen Shawn on getting out of music writing ruts, by Briee Della Rocca

Composer, author, pianist, and faculty member Allen Shawn published his fourth book and second biography —Leonard Bernstein: An American Musician. He has previously published Arnold Schoenberg’s Journey, Twin: A Memoir, and Wish I Could Be There: Notes from a Phobic Life. Whether on assignment or propelled by an internal need to share his story, Shawn describes the act of writing as his own “attempt to mediate between something difficult and an audience.” But, despite having written two very different and difficult memoirs about his own life, he says if you want to really know him, listen to his music.

Julia Bartha did just that. A German pianist who had only met Shawn once, Bartha connected with him across oceans by recording 19 of his works. The album, Allen Shawn: Piano Works, was released in October by Coviello. We spoke with Shawn about his work, his teaching, and the latest album of his compositions.

You are a composer and an author, and people have connected with you on both accounts—listening to your music and reading your books, two of which were memoirs. But you’ve said that if a person really wants to know you they’d have to listen to your music. Can you explain why that is?

Well, I have an urgent need to reach people with my music. It’s what I deeply care about and need to share. It is one’s autobiography in some very deep sense. It’s not one’s autobiography in the sense of what you want people to know about your life. It’s better than a biography. It is a seismograph.

When you’re writing music you are a raw human being—a complete person. You’re in the service of art form and whatever comes out is what you’re going to work on. There’s no censoring. When you listen to your material you will hear it telling you what it needs to do. If you follow that through it will reveal you. It’s not that you have any intention of what it will say or what will be revealed. In fact, very often it reveals something you did not see in yourself, the way a photograph can.

What happens when you compose something and other people play it? When Julia Bartha recorded your work, did she reveal something you didn’t see when you wrote the pieces?

It’s interesting because I play the piano and I perform my music, but when Julia plays those pieces she does them better than I do. She’s better. She restores them to what they really are. When I perform them I take them for granted a little bit, where she is amazed by them and she reveals what they are. When we play our own music there’s a danger that it’ll be a narcissistic exercise in self-regard. As a result we “present” the music, perhaps a bit impersonally, as if to say: here’s what it is. Hope you like it. Whereas somebody else can really go to bat for it, and get behind it in a different way.

What is it about music that you feel drives a connection that writing can not capture?

Music is non-verbal. It’s abstract. Of course, people receive it as deeply emotional, but what those emotions are and what you’re actually expressing can not be put into words. Music is physics being harnessed to make art. It does things neurologically that we don’t even understand. That’s part of the fun—that you don’t know what it is. I teach about it to some extent, but we don’t really know what it is. In fact, when you read analyses of music, when you get to the end they have not explained the music because we don’t actually have language for it.

How do you teach something that we don’t have a real language for— that we can’t understand entirely?

Well, I think of teaching in terms of shocking the students. I really believe that our culture is so barren that it’s quite likely that until they have gotten to college, students have never been shocked at how great art can be. When I put my teaching hat on, I’m there to try to somehow or other give them the experience of seeing what went into the great works and that they’re not going to necessarily easily find them in our society, because there’s no conscience guiding society. Society is like capitalism; it’s guided by what works at that particular instant. There’s no overriding conscience behind it that says, “All kids deserve to hear Beethoven.”

I feel obliged to try to compensate for this. That’s my responsibility. I’m there to help the students realize that it’s possible to do something of real value, not just transient value. I’m there to reveal the amount of thought and dedication that went into wonderful pieces of music, and the selflessness that went into them.

That’s my true philosophy behind teaching. I don’t mean “shock” in a horrifying way, but I want people to be awakened to what’s possible and also to realize how hard it is to grasp it, or achieve it. This is the opposite of what students might think Bennington is. On the one hand you could say, hey, you have this inside you or all you need to do is work hard and you’ll get there, but in a way I’m not saying that. I have no idea who’s going to do what in their later lives. I don’t know which of the students is capable of this or that, but I do believe that everybody should encounter great work. I feel that knowing what has been done by others inspires and empowers us to do whatever it is we have in us to do.