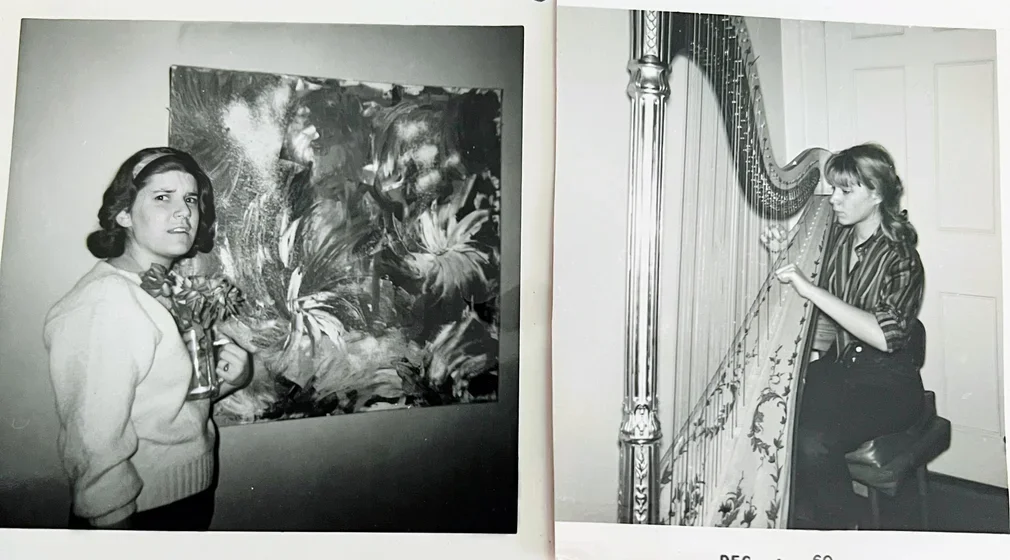

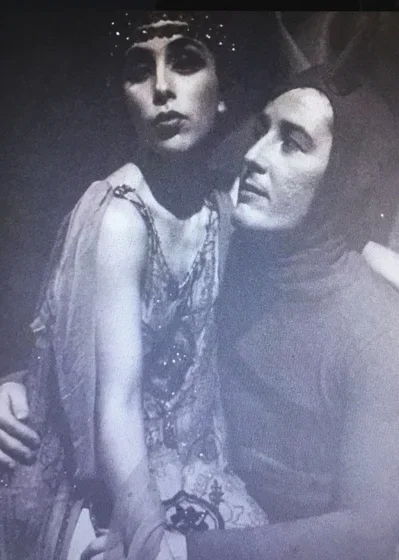

Bennington College in the Sixties

An encouraging place for rebel types.

Bennington alumni of the sixties remember the smell of the countryside in the fall; being “blown away” by seeing modern, non-representational art for the first time; meeting for class in house living rooms; and enjoying regular concerts of chamber music over dinner in the Dining Hall. They remember being inspired to learn Mozart’s Requiem after hearing faculty member in literature Howard Nemerov whistle it as he walked across campus and playing music faculty member Louis Calabro’s “Ceremonial March” in their bare feet at their own graduation. They remember overhearing salacious conversations while waiting for their houses’ shared telephones and waiting in line to call home when President Kennedy was assassinated.

They heard Robert Frost read his poems and the cacophony of typewriters coming from each room when papers were due, especially just before Long Weekend. During a drought, they remember the dance students “in a big circle performing mystic rites on the lawn to make the rain happen.” How wearing blue jeans was rebellious everywhere but here; even faculty members wore jeans. (“It was an encouraging place for rebel types,” said Joan Tower ’61.) Students knew how to fix a broken audio tape with a razor blade and Scotch tape. And they remember marveling at the big view at the end of Commons Lawn.

Many keep mementos from their time at Bennington. Kate Rantilla ’67 reads over the speech that President Fels gave to her and her classmates as they entered Bennington for their first year. Judy Bond ’61 still has a music stand she made with Robert “Woody” Woodworth, a faculty member in biology. “He and his wife would give concerts—he on banjo or guitar, she on piano. She was a very proper New Englander, but when she played, it was jazzy, full of life,” said Bond. “They were examples of how academics can also be artists.”

The most memorable of all aspects of Bennington College in the sixties were the faculty and their power. In addition to Calabro, Nemerov, and Woodworth, the names of faculty members glint atop most stories about Bennington at that time: William Bales (Dance), Ben Belitt (Literature), Henry Brant (Music), Lou Carini (Social Sciences), Ruth Currier (Dance/Drama), Julian DeGray (Music/Visual Art), Francis Golffing (Literature & Languages), Paul Gray (Drama), Bernard Malamud (Literature), Jack Moore (Dance), and Martha and Josef Wittman (both Dance/Drama), to name a few. Some were demanding and opinionated. Many were famous in their fields or in general.

“I feel in some essential way I have never left Bennington.” Fran Bull ’60

MYTHICAL FACULTY

Stanley Edgar Hyman, husband of famed writer Shirley Jackson, taught the hugely popular Myth and Ritual in Literature, known affectionately by the late sixties as Myth, Rit, Lit. (The class was the most commonly mentioned detail among the sixteen interviews for this story.) “Everyone wanted that class,” remembered Janet Warner Montgomery ’65. “It met in Barn 1 and must’ve been the biggest class on campus. It enabled a thinking pattern I never had before—comparative thinking. Myth, ritual, Freud, the Bible, Lead Belly songs—it was a pile-up. Incredible.” She read the whole Bible for that course while riding the commuter train in New York. “That class broke down a few shibboleths from my Christian upbringing,” she said, laughing.

Writer Roxana Robinson ’68 remembers Hyman as “a wonderful physical presence.” “He was small and kind of slightly portly, and he had that beard, and he smoked all the time, and often he would start to light a cigarette on the wrong end, and the whole class would be rapt and breathless, waiting to see if he would figure it out before he actually lit the filter end or not. He was so absorbed in his subject, completely engaged by the stories he was telling us about the ancient world.”

Nina Straus ’64 struggled in Hyman’s class at first, overwhelmed by the interdisciplinary intensity. But Hyman responded favorably when she wrote a comparative analysis of Maccabees I and Maccabees II. “He said to me, ‘You did it. You’ve got it.’ And I thought, ‘Yeah. I can do this.’ It gave me enormous confidence.” Straus went on to an impressive career as a feminist literary scholar, critic, and professor at Purchase College, part of the State University of New York system. Indeed, faculty comments, in person and in writing, had the power to turn lives.

POWERFUL COMMENTS

Robinson ’68 took a creative writing workshop with Bernard Malamud, one of the best-known American authors of the twentieth century. “He was precise, measured, also sort of small and neat, and he gave us this powerful sense of order as a creative writer,” Robinson recalled. “He said, ‘Do not wait for the muse to come to you. You write every day. You have a particular time, and you write during that time. It was a powerful introduction to the creative life.” Robinson followed Malamud’s advice and is the author of seven novels, three collections of short stories, and the biography of Georgia O’Keeffe.

The comments were not always perceived positively. Betty Aberlin ’63, who appeared for 30 years on a popular children’s television program in addition to working as an actor on other shows and movies, remembers turning in a sonnet to Hyman and receiving his feedback: “Cousin Betty, you will never be a poet.” “It was a blow to the heart,” she said. She stopped writing poetry altogether only to learn years later that he meant it as a compliment. It was based on the comment (“Cousin Jonathan, you will never be a poet.”) that poet John Dryden had given his cousin Jonathan Swift. Aberlin’s book, The White Page Poems, written in response to and appearing in the same volume as George MacDonald’s 1880 Diary of an Old Soul, was published in 2008.

Nor were the comments strictly academic. Houston remembers a childhood filled with instances of being noted as less attractive than her younger sister. She grew up thinking that she was truly ugly. One bright beautiful morning, she was walking across the green toward Jennings Hall for class when she saw Malamud approaching. “He stopped and he looked at me, and he said, ‘You are beautiful. You are just stunning.’ And he patted me on the shoulder, and he kept going.” Houston paused, “Even as I tell you about it today, I tear up a little... all of a sudden all the ugliness from childhood fell away.” She emphasized, despite Bennington at that time turning a blind eye to many faculty-student relationships that would now be considered scandalous, the moment was “entirely appropriate and deeply human. There was absolutely nothing untoward in it.”

Sex in the Sixties

On the average Friday or Saturday night, students on the second floors of the New England clapboard houses around Commons Lawn on the then all-women’s campus would hear the male students from Williams yell “Anyone want a date?” “It was a little like a meat market,” recalled Elinor Bacon ’63.

“We used Williams boys for our productions, and they used Bennington girls for theirs.” Betty Aberlin ’63

Victoria Houston ’67 lived in Stokes. “That’s how I met my friend Ellen (Safir). Ellen was dating this guy from Williams, but he didn’t have a car, and so the two of them hooked me up with his friend, who did have a car. He turned out to be my first husband and the father of my three children.”

Men were allowed in the houses at most hours and even in the rooms until 10:00 pm. One student remembers going into the bathroom only to hear a rich baritone voice singing in the shower.

While the Williams students were “too jockey” for some, other students were as eager as the boys. For some years, Lois Wilkins ’67 remembered there being graffiti painted on the campus side of one of the stone columns marking the entrance. It said, “only 19 miles to go.”

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

Students often entered Bennington with the wider culture’s preconceived notions about what women could do. “I grew up thinking girls were dumb because that’s what the age was,” said Louise Reichlin ’63. Similarly, Fran Bull ’60 recalled having “encountered the attitude that women did not make serious art.”

Many other women’s colleges at the time were focused on educating wives or “well-rounded” young women. “I never heard that at Bennington,” said Gail Evans ’63. “It wasn’t about being well-rounded. Even studying the arts wasn’t about being well-rounded—it was about expressing a different part of yourself and your emotions.”

Once acclimated, “we women at Bennington at that time did not feel constrained by our gender,” Bull recalled. “We were surrounded by a lot of brilliant women who did different things,” said Evans and soon learned that “women were as smart, independent, and talented as men—and we should go get what we wanted, not what somebody told us we were allowed to have.” She continued, “The message was: figure out what you love and what you are brilliant at—and go for it.” Lois Wilkins ’67 added, “Perhaps the greatest lesson I learned was that I could do anything I aspired to and was willing to work hard for.”

Brenda Corman Alpar ’62, mother of current Bennington Ethnomusicology faculty member Joseph Alpar, became a nationally recognized Middle Eastern dancer and dance teacher. She owned a studio and a night club in Manhattan and later became the music, art, and drama teacher at the Perelman Jewish Day School in the Philadelphia suburbs, where she composed hundreds of songs, musicals, and operettas for children. “I always give full credit to Bennington for introducing me to the philosophy that if something intrigues you and you want to pursue it, that’s all you need. Go ahead. If the motivation is there, nothing can stop you.”

Graduates often found the limiting attitudes outside Bennington when they left. For a while, Alpar was the only woman in the master’s degree program in Music Composition at Juilliard and encountered some pushback from her male classmates. “How can a woman compose music,” she heard classmates say, “when their brains are not the right shape, and they don’t have any capacity for abstract thought?” Despite the hostility toward the idea of a woman in this field, she thrived as a composer. And slowly the world changed. Graduates went on to have powerful careers in government, scientific research, the media, music, and as writers, even as many raised families.

SOCIAL CHANGE: THEN & NOW

Alumni from the sixties see some similarities between their time as students and the current moment. The ongoing struggles with racial inequality and political corruption were felt then and now. “The 1960s were a time of great passion. Civil rights. Fair Play for Cuba. Today, there are echoes. Nixon’s enemies list, the imperial presidency—you can draw a line from that to now,” said Evans. “We had a sit-in at the Howard Johnson’s in Bennington. The poor guy running it was like, ‘Anybody who wants to eat here can.’ We had turmoil and action but not a lot of fear,” said Evans.

Kate Rantilla ’67 remembers community organizing with Students for a Democratic Society in Newark, NJ, and participating in the first major Vietnam protest in April 1965. Back then, Rantilla noted that events coverage happened more slowly; there was more time to reflect. “Now, instant communication changes the nature and pace of activism,” she said.

Alumni express dismay over erosion of democratic norms and civic trust. “There are moth holes in the fabric of society,” said Rantilla. “Students in the sixties may have criticized the government and police, but they still believed in the system’s core structures.”

“Back then, even when we protested, it still felt like America had ideals. Now, it feels like everything is on the table,” said Bacon. Wilkins added, “I don’t think anybody [back then] thought we were going to actually lose the country that was run by its constitution with checks and balances, but we have, and it happened so fast.”

A LOVE OF CHANGE

Bennington fostered a love of change in its sixties alumni. “There was a strong emphasis on thinking critically, writing, and changing one’s mind without stigma,” said Wilkins. “You can change your mind whenever you want. You don’t grow up being taught that. If it makes sense to change your mind about something, do it.” Rantilla said the biggest thing she carried forward was the idea that “it’s okay—and even good—to change course.” Many changed concentrations as students, including Joan Tower ’61, who switched from Physics to music composition. And they changed careers midstream: journalism to education to pottery, Chinese relations to urban planning, music composition to Middle Eastern dance.

Welcoming change allowed for uncommon resilience among many alumni. “If something didn’t work, you open a door and try a different pathway,” said Louise Reichlin ’63. That lesson has seen her through a 50-year (and going strong) career as a dancer and choreographer, a professor of movement training, and founder and director of the non-profit dance company Los Angeles Choreographers & Dancers.

The willingness to change also led alumni to ever-expanding learning opportunities. Now in their eighties, they are master gardeners, Audubon volunteers, and students of ukulele. Aberlin debuted as a playwright with Annie & Zoe in 2025. Myrna Blyth ’60, editor of the nation’s most widely circulated magazines, including Ladies Home Journal and Family Circle, pursued a master’s degree in Liberal Arts at Johns Hopkins during the COVID-19 pandemic while working full time as the senior vice president and editorial director at AARP Media. She graduated in May 2025 and retired in June. “I’m taking courses at the University of Chicago at the moment,” she said. Bacon recently qualified for a national hot yoga competition. “I came in third out of three, but I made it to nationals. I asked if they had an 80-plus category—they just laughed.”