Unscripted Paths

Bennington College’s Theater Training and Its Impact

The performance wing of VAPA is home to the cavernous spaces of Margot Tenney, Lester Martin, Martha Hill, and Greenwall. But it also houses a theater training program that wears its ubiquity on its sleeve. Ranked #3 by The Princeton Review for “Best College Theater,” Bennington’s Drama discipline eschews typical theater education formulas that confine students to just one concentration.

Boasting such alumni as award-winning actors Peter Dinklage ’91, Carol Channing ’42, Twilight Saga screenwriter Melissa Rosenberg ’86, Succession costume designer Michelle Matland ’84, and many more, Bennington’s Drama discipline encourages students to explore broadly. This sense of experimentation brings bold and diverse work to department stages and launches careers in the worlds of theater, film, television, and literature. The Bennington College education, intensely collaborative and responsive to the world beyond campus, is also a unique incubator for theater artists, one where they can forge original paths and dive deep into the elements of theater that excite them most. This model of inquiry leads Bennington alumni into exciting careers, and it all starts with students advocating for themselves.

PECULIAR PEOPLE

Kirk Jackson, a longtime acting and directing faculty member at Bennington who retired in spring 2025, says the “original ingredients” students bring to the Drama discipline foster a mutually dynamic experience for both faculty members and students. For Jackson, Bennington “is a magnet for peculiar people, [so while] we stress rigor around the basics,” there is no set template for a Bennington Drama student. Citing playwriting faculty member Sherry Kramer, who also retired in the spring, Jackson says the faculty lead with an approach of “here are tools, learn the tools, do what you want with them, [and] maybe break a couple of tools to come up with your own voice.” The key, for Jackson, is that the students have an “invitation to fail or stumble in an interesting way.”

Kaiya Kirk ’20, who now works as the Executive Director at Bennington Theater, affirms, “in opposition to a standard theater program, there is no ‘dramatic focus.’ [Now,] I have a breadth of tools in my toolbox that I wouldn’t have” had she gone to another institution. Bennington’s unique approach means that students can fill that toolbox from multiple angles. In the traditional sense (at least as traditional as Bennington can be), the experimentation begins with classwork. Abigail Geoghegan ’09, who now works as first assistant costume designer on the Hulu series Only Murders in the Building, cites her work with the late faculty member Danny Michaelson as formative in this sense. “Costume Projects with Danny Michaelson changed my life,” said Geoghegan. The way he structured projects made it easy for Geoghegan to develop a workflow that she carries to her film and television work. Michaelson’s Light, Movement, and Clothes course, which enrolled both Dance and Design students, was “a cool experience” for Geoghegan, as the course required that students “put [them]selves in another’s shoes” and created a new awareness for designers collaborating with performers.

The devised work of Tenara Calem ’15, a Philadelphia-based self-identified “theatermaker,” proves that Bennington’s encouragement of interdisciplinary study influences an artistic career in unique ways. Associate Director of CAPA and faculty member David Bond’s “transformative” class How to Study a Disaster left a lasting impression on Calem and led her to create a devised performance of the same name. Calem’s piece, conceived in partnership with New Orleans native Jo Kramer in response to Hurricane Katrina, asked “how do communities and governments tell the stories of, make sense of, and memorialize ecological disasters, both natural and man-made?”

Bond’s course’s approach to the subject material sent her down the path of researching how we might put the questions that we ask about disasters and conflicts “into theatrical space.” Bennington’s coursework transcends traditional artistic education when put in conversation with courses outside the arts.

THE THEATER PLAN

Calem’s Plan, “The Storytelling of Political Narrative,” made for a unique fusion of her work in Society, Culture, and Thought with Sherry Kramer’s playwriting courses. She recalls that the Plan Process gave her permission to pursue the various streams of her coursework “independently and see what cross-pollination there was,” leading to an overarching question of “how we make sense of the political worlds around us.” Kirk, meanwhile, wrote her Plan in Black studies and “theater in general” as a means of exploring representation in all its forms in the theater world. Geoghegan had set out to write her Plan in Drama and Literature, but she recalls that “when I first presented it, my Plan committee [saw] that

I was more passionate about the Drama side.” This feedback from her Plan committee allowed her to restructure her Plan to focus on “character in general and the exploration of character,” which she reports has served her work as a designer. The Plan Process brings students and faculty together on the direction of a student’s coursework, one of many forms of collaboration that most traditional programs don’t offer to their early-career artists.

THE PRODUCTIONS

Another avenue of development central to the Bennington Drama experience are the productions presented every term. Faculty-directed productions, on which students work for class credit, are presented alongside less formal student-led productions, which take place in myriad spaces on Bennington’s campus.

Alexander Dodge ’93, who has gone on to work as a set designer on Broadway and at the Metropolitan Opera, among other places, cites Bennington students’ use of unconventional spaces as an early inspiration.

“VAPA was such an inspirational space, the likes of which I haven’t seen since,” as was “the beautiful Vermont countryside,” said Dodge.

However, it's a production he worked on of Alan Bowne’s Beirut in the basement of Bingham House is one he remembers fondly. For Dodge, the fact “that it was so student-driven and student-run” set the work of Bennington students “apart from everything else… that was the whole idea of it. You had to be self-motivated.”

Calem recalls acting in an adaptation of Great Expectations directed by Jackson, as part of “one massive ensemble, moving puppets, set pieces, creating the visual world” as particularly exciting for a young Drama student. “At the time, I remember feeling so lucky… to do something that wasn’t living-room theatre,” where students were an integral part of the creative process at all levels.

THE FACULTY PRACTITIONER

Geoghegan affirms how rewarding it was to collaborate with Bennington faculty. which now includes faculty members Maya Cantu (dramaturgy), Michael Giannitti (production management and lighting design), Tilly Grimes (costume design), Dina Janis (acting), Jean Randich (directing), and Sue Rees (set and projection design) and technical instructors Richard MacPike (costume design) and Seancolin Hankins (set design).

Bennington’s teacher-practitioner model requires that faculty members maintain a career in the field in which they specialize. Faculty members’ constant reengagement in the professional world ensures that students work closely with professionals attuned to the real-world applications of work in the theatre, not just grinding at coursework. Working as an undergrad alongside faculty members with extensive professional credits meant she was able “to learn how things function in a professional way.” For a student sorting out where they may end up in the theatrical landscape, Bennington’s teacher-practitioner model means that students can learn from faculty as they work together, not just in the classroom.

For Kirk, the value of Bennington’s teacher-practitioner model is that faculty members “know what the culture of producing is.” As they collaborate, advice for how to make a life in the arts is woven into the process. In Dodge’s view, Bennington’s “all hands on deck, all the time” ethos means that a Bennington Drama student graduates “know[ing] about a lot of things” they can apply to making theater outside of the College.

Elizabeth Williamson ’99, Artistic Director of Geva Theatre in Rochester, New York, forged a path at Bennington that put this ethos into action. Referring to a conversation she had with her advisor, former faculty member Janis Young, Williamson recalls, “I remember, at one point, Janis saying to me, ‘Oh, you’re more a projects person than a roles person.’” Bennington’s project-oriented focus created opportunities for her to pursue academia and led to her work as a dramaturg at prominent regional theaters.

“Having to figure out what you need to learn and how to put it all together… was phenomenal training for a career in the theater.” In Williamson’s experience, “you have to make it all up for yourself” in the professional world.

SELF-DIRECTION

Bennington’s self-directed learning approach, where students receive narrative evaluations alongside (or even in place of) grades, also prepares its graduates for the precarious elements of a life in the theater. Maya Macdonald ’07, a New York-based playwright and educator whose play Brunch was produced by The Playwrights Realm in 2019, says Bennington’s approach influences her to this day.

“Having a space where you’re not reaching for grades,” Macdonald says, means “you know how hard you’re working [and] when to push yourself more. That self-guided view has motivated me in working as an artist.”

According to Macdonald, playwrights continually evaluate their own work, particularly in early developmental stages, before readings or productions. Self-evaluation, Macdonald says, “is so important in staying focused…. The work [is] what you can control. I’m creating things that people may not know they want to see,” and the self-advocacy skills she developed at Bennington serve her work to this day.

Kirk’s time at Bennington College has taught her “how to have a list of one million things due, how to prioritize, not to linger or obsess.” Kirk’s “ability to weigh tasks and be self-sufficient” is crucial in running a small arts institution like Bennington Theater. Even something as boilerplate as applying for grants has brought to mind her Bennington education. She recalls a class, Writing to Describe, that she took with faculty member Dana Reitz as particularly valuable for her administrative work. “She would have you go look at something and write 200 words on it.” Reitz would insist, “‘no meaning, I don’t want meaning, I just want you to describe it.’I think about that a lot,” she says, particularly when working to serve the needs of her institution.

FINDING A PLACE

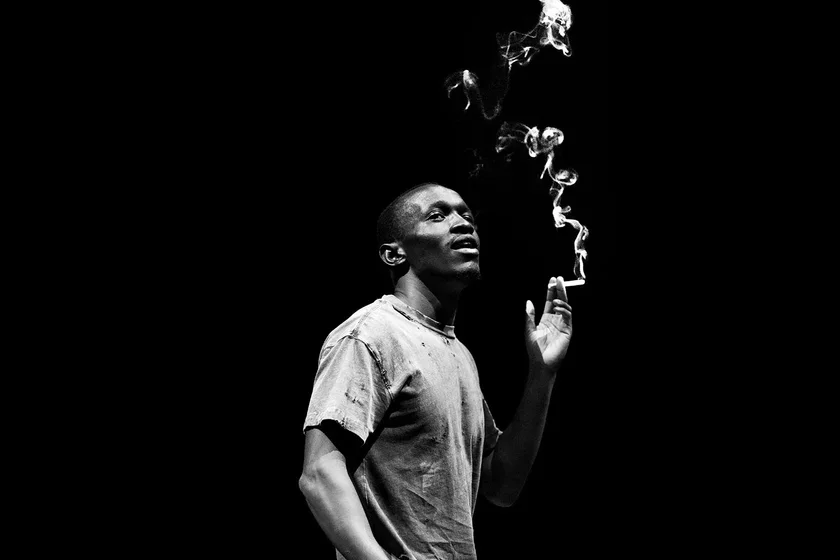

Shawtane Bowen, a writer, actor, and improviser who joined the Bennington Drama faculty in fall 2022, has an eye toward keeping Bennington Drama sustainable for the next wave of students. “How do we make this more holistic and sustainable?” is the big question among faculty at the moment. The theater landscape still hasn’t quite recovered from COVID-related shutdowns in 2020, and the needs of theater artists in training have changed. In Bowen’s eyes, “the discipline is headed towards a more… collaborative, DIY, punk-rock aesthetic in terms of making do with less.” Bowen says that students and faculty alike are asking themselves, “How do we still create something that tells a story and has some type of meaning for the audience?” Citing his colleague Jenny Rohn’s recent Grotowski-inspired production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and his own focus on improv, Bowen believes that Bennington’s mode of theater training is evolving in response to the ever-changing arts landscape. Ultimately,

Bowen says, “we’re trying to give everybody an opportunity to… find their place within Drama. That’s one of the beauties of the program.”

Drama at Bennington College is unique because it can’t be pinned down. Every student who steps onto a stage, into a booth, or into a classroom in the theater wing in VAPA brings their own interests, desires, and talents to their work. Geoghegan says working with “a faculty member who is also a professional theater maker is not something that many 19-year-olds get to do. Being treated as an adult and not just a student in those moments” gave her the tools she needed to build a life in the arts. By providing its students with ample collaborative opportunities, Drama at Bennington creates multifaceted artists who graduate ready to create art in their own unique way.

As their paths diverge from Bennington, the value of collaboration and flexibility make themselves clear. Calem says that the “gritty, unapologetic, maximalist attitude in the Bennington ethos” has been a guiding force for her career. “It can’t be overstated how much Bennington continues to influence the way I move through the world.”