The Seeds That Became Stories

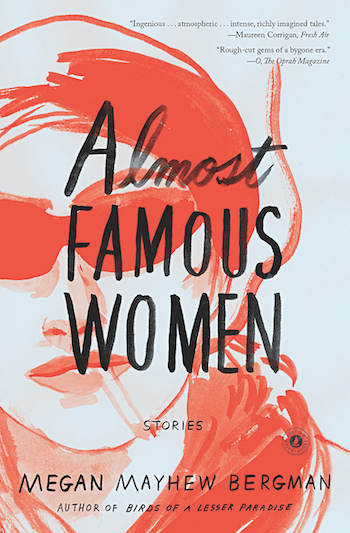

An excerpt of the author notes from Almost Famous Women wherein Megan Mayhew Bergman MFA '10 describes the initial inspirations for her stories.

The Pretty, Grown-Together Children: I heard a whisper or two about the Hilton twins while living in North Carolina, then came across an entry about them on RoadsideAmerica.com.

The Siege at Whale Cay: I devoured Kate Summerscale’s incredible, must-read biography of Joe, The Queen of Whale Cay. Further research has led me to the exceptional Time Life photoshoot of Joe and Whale Cay, as well as videos of Joe’s races, which can be found here. I also found inspiration, though not philosophical agreement, in Helen Zenna Smith’s novel about the female war experience, Not So Quiet…

Norma Millay’s Film Noir Period: A friend turned me on to Nancy Milford’s biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Savage Beauty, and like many young women I was perhaps, at first, fascinated more by her biography than by her work. When I was a resident at the Millay Colony for the Arts at Steepletop in 2007, I became acquainted with the wild stories about Edna’s sister Norma, and found myself returning to her in my imagination, particularly the fact that she was an actress in her own right, with the renowned Provincetown Players, and inhabited her sister’s estate for decades. Norma was a true force, and it was her presence I felt so keenly at Steepletop. Other resources include Cheryl Black’s The Women of Province-town, Daniel Mark Epstein’s What Lips My Lips Have Kissed, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Collected Poetry, and her Collected Letters edited by Allan Ross MacDougall.

Romaine Remains: I came across this haunted, unusual figure in many books about Paris: Wild Heart by Suzanne Rodriguez, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation by Noel Riley Fitch, but most important, Meryle Secrest’s (out of print) biography of Romaine, Between Me and Life, titled after Romaine’s sentiment that her dead mother stood between her and living happily. I have framed prints of Romaine’s line drawings, which I cut from Whitney Chadwick’s catalog of Romaine’s work, Amazons in the Drawing Room. Chadwick points out an element of Romaine’s work that made a deep impression on me—the unusual depiction of “heroic femininity.”

Hazel Eaton and the Wall of Death: Let me be intellectually honest here—Internet rabbit hole.

The Autobiography of Allegra Byron: I first heard of Allegra when I studied at Oxford for a summer, and also read Benita Eisler’s Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame. Furthermore, Dolly Wilde’s fascination with Byron and her similarities to his daughter are pointed out in Oscaria, the privately printed book of remembrances about Dolly. Both girls were given over to convents at an early age, which was not particularly unusual at the time but could not have been a welcome experience. Allegra’s story took off in my head years later, after I had children of my own, and could get more inside the head of a toddler.

Expression Theory: I saw a stunning photograph of Lucia Joyce in a hand-sewn costume, which led me to Carol Loeb Schloss’s biography, Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake. I found myself curious about the moment family members decided Lucia was deeply troubled; throwing the chair took on significance.

Saving Butterfly McQueen: I don’t remember how I first heard of Butterfly, but when I found out that the Gone With the Wind star was an atheist, and had hoped to donate her body to science, I was intrigued, and couldn’t help but imagine the waves of patronizing conversation she must have endured.

Who Killed Dolly Wilde?: Bennington alumna Joan Schenkar’s biography of Dolly Wilde, Truly Wilde, opened a door in my imagination, perhaps because she invited her readers to do just that, ending the introduction this way: “I have only been able to bring her to you complete with missing parts. It remains for you to do what Dolly could have done so beautifully for us all: Imagine the rest.” Other sources include Oscaria, the private volume of recollections Natalie Barney had printed in Dolly’s memory, which I am thankful for Bennington Librarian Oceana Wilson’s help in obtaining access to. Additionally, Neil McKenna’s The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde and Richard Ellmann’s biography.

A High-Grade Bitch Sits Down for Lunch: When my mother-in-law passed away in 2009, it took me two years to read her favorite book, West with the Night. My mother-in-law was brave and athletic, a horsewoman, a young pilot, and a motorcycle-driving veterinarian—like Beryl Markham, a boundary breaker. I now teach Beryl’s memoir, and celebrate the fact that it’s one of the few books where we see a woman portrayed as an active hero of her own adventures with the absence of a central love story. While Beryl was a record-breaking pilot and author (not without authorship controversy, mind you), she was also Africa’s first female certified horse trainer, a feat that required grit, fearlessness, and athleticism. I like to see women working in literature, using their bodies. I also read biographical work on Markham from Mary S. Lovell and Errol Trzebinski, as well as Juliet Barnes’ The Ghosts of Happy Valley.

The Internees: While researching an article about environmentalism and makeup, I came across an anecdote about the boxes of lipstick from Lieutenant Colonel Mervin Willett Gonin, who helped liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. Later, a friend, Henry Frechette, sent me the picture of Banksy’s visual reinterpretation of the internees wearing lipstick. This, to me, is an unpretty and profound take on fame and femininity.

The Lottery, Redux: I was asked by McSweeney’s to write a “cover story” of a classic, and I chose Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery, because it’s the first short story I remember reading, and I drive past her house in Bennington often. I knew I wanted to give homage to it with a matriarchal lineage in mind, and the idea that we pay for the mistakes our forebears make.

Hell-Diving Women: Oxford American asked me to write an essay on the International Sweethearts of Rhythm for their annual music issue. I had the pleasure of losing myself in research, and then finding out that the band played long ago in my hometown of Rocky Mount, North Carolina. After the article I found myself still dwelling on the material, and wanting to write a story. For further research, see D. Antoinette Handy’s (out of print) biography on the Sweethearts and Jezebel Productions’ short documentary Tiny and Ruby: Hell-Divin’ Women (the name of Tiny and Ruby’s post-World War II band).

There are other books that have enriched my imagination, including but not limited to: Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy by Carolyn Burke; The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall; Women of the Left Bank by Shari Benstock; Nightwood and Ladies Almanack by Djuna Barnes.