Building in the Round with Many Fronts

How the renewal of Commons is driven by the philosophy of a Bennington education, by Heather DiLeo

In the 1950s, an alum of Bennington’s fourth graduating class, Elizabeth (Betty) Mills Brown ’39, wrote a moving public poem considering the impact of plans to enlarge the campus along with the student body (from 300 to 600). Brown, by then an architectural historian and member of the College’s Architecture Committee, assessed the relationship between the College community and the spaces it inhabits. She challenged her colleagues to reject the American tendency toward “academic suburbia”:

With a Science Building here,

surrounded by a sea of green lawn,

and an Art Building there,

surrounded by a sea of green lawn,

and a Theater out there,

surrounded by a sea of green lawn,

and everything connected up with diagonal paths and juniper bushes.

There’s more than one explanation for why Bennington looks and feels different from other American campuses—or why the buildings and grounds seem not merely purpose-built but expressive of the school’s educational philosophy. This was largely by design, thanks to advocates such as Brown—but not entirely. Chance and even misfortune played a role in shaping the campus.

Architecture faculty member Don Sherefkin points out that, as the first school to take art as seriously as every other subject of academic inquiry, the College infused the campus with the imperative to explore and collect influences that enrich artistic practice. Most of the school’s buildings are designed to encourage the kind of experience the studio artist working in VAPA has. But before VAPA or Dickinson Science Building were constructed, exposure to a vast variety of students and work was inevitable. A painting student could not help but pass the work of a scientist or a philosopher before arriving at their studio in Commons. And yet even as the College expanded, it has maintained for students the sense of serendipitous discovery.

“I’ve always found it interesting about the campus that, even though it’s very symmetrical in its planning, there’s really no front door to any building. You sort of always enter diagonally on corners. You have to create your own path,” says Sherefkin.

That path is all the more interesting when we consider the plans of the College’s original architects, the Ecole des Beaux Arts–trained, Boston-based, John Ames and Edwin Dodge. Ames and Dodge, who worked on buildings for Smith College and Harvard as well as Bennington’s Commons and the original student houses, modeled their plans for Bennington after Thomas Jefferson’s neoclassical design for the University of Virginia. They projected a tightly logical American college, with Commons, serving as the head of the organism, at the top of a splendid lawn, flanked by two rows of mirror-image, facing dormitories.

However, Ames and Dodge drafted their first plans under the assumption that they would build opposite Old First Church on 45 acres owned by the Colgate family in Monument Circle Drive of Old Bennington. But this was not to be. Fortune intervened in the form of the stock market crash of 1929, causing the Colgates and other patrons to revoke their gifts to the College. Happily, the Jennings family stepped in, donating the 140 acres that became the core of today’s College campus.

Naturally, Ames and Dodge had to adjust to the new landscape and straightened financial circumstances— replacing their projected three-story brick dorms with wood-clad student houses and scrapping designs for a gymnasium and swimming pool. They had also to scale back their rather grand conception of Commons—complete with a columned, domed rotunda and a substantial library.

We’re making a building that rightly belongs at the geometric center of campus; one that is as open and accessible from the north, east, and west as it is from the south. A building in the round, that has many fronts, and one that programmatically serves as the embodiment of the Bennington experience. Martin Finio

Although situating the College on Monument Circle Drive might well have been a boon for Old Bennington, there’s no doubt that the country’s financial collapse proved providential for the school. “Having this larger piece of land meant that when the College expanded, it could be much more adventurous—all of the subsequent buildings are more appropriately modern for a progressive college,” says Sherefkin. “Rather than being a very fancy school with a progressive agenda, we became a school that had to make do with whatever it could. We are used to figuring out and making do with what we’ve got on hand. When you’re converting chicken coops into faculty dwellings, you have a different perspective on things.”

Commons was the nucleus of the new campus at the College’s founding: the focal point of its design and the center of academic and social life. It was where residential and academic space coincided, serving not only as dining hall and meeting place but housing the architecture and painting studios on its top floor—flooded with light from large north-facing windows, as well as a storied performance stage.

In its vivid first half-century, Commons was where Martha Graham invented a new language of movement and where Gunnar Schonbeck’s students experimented on handmade instruments: hanging pipes, plywood guitars, and disassembled pianos.

Over time, as the College expanded, visual and performing arts found new homes on the campus, and Commons’ third floor was ultimately closed in 1985. From then until 2017, Commons was operating at two-thirds of its capacity. After 85 years of adaptation, particularly on its north end, it had been subdivided—to include things such as Health Services and the post office—and particularized.

“It lost the original clarity of intent it had when it was put into place. It was very hard to understand the building as a thing in the absence of all of these accretions—like an ocean rock where sand has crystallized around a bunch of shells,” says architect Andy Schlatter, Associate Vice President of Facilities Management and Planning.

While it remained a vital gathering space, where students and faculty and staff would converge for meals, the center of campus no longer served as a vital estuary of ideas and work that it once was. It became clear to the College the space it most missed was one in which all facets of student academic and social life and all members of the community would come together. And while the imaginative Betty Brown was writing 50 years ago, as the College was planning for VAPA, her thinking is still relevant today:

Why not think in terms of a continuous whole,

something that would be neither one big

building nor forty small ones, but both—

something supple and wandering—

partly indoors and partly outdoors ...

all this not exactly one building,

not exactly many, not exactly a building at all,

simply a stream of energy rising and falling

with areas of concentration and areas of expansion.

REIMAGINING

Practically speaking, the reinvention of Commons began four years ago—but is informed by the history of the College and at least 20 years’ worth of community members’ ideas. The interior demolition of the building revealed its three-dimensional presence and possibility, a much larger space than anyone anticipated and even previously hidden fireplaces. The project is currently at the halfway mark and is expected to be completed within the next year.

“It’s the sort of building, both in its original form and in renovation that has a real diversity of spaces, in terms of scale and feel and materiality. Our task is to recognize the inherent qualities of the building and try not to get in the way of them,” says Schlatter.

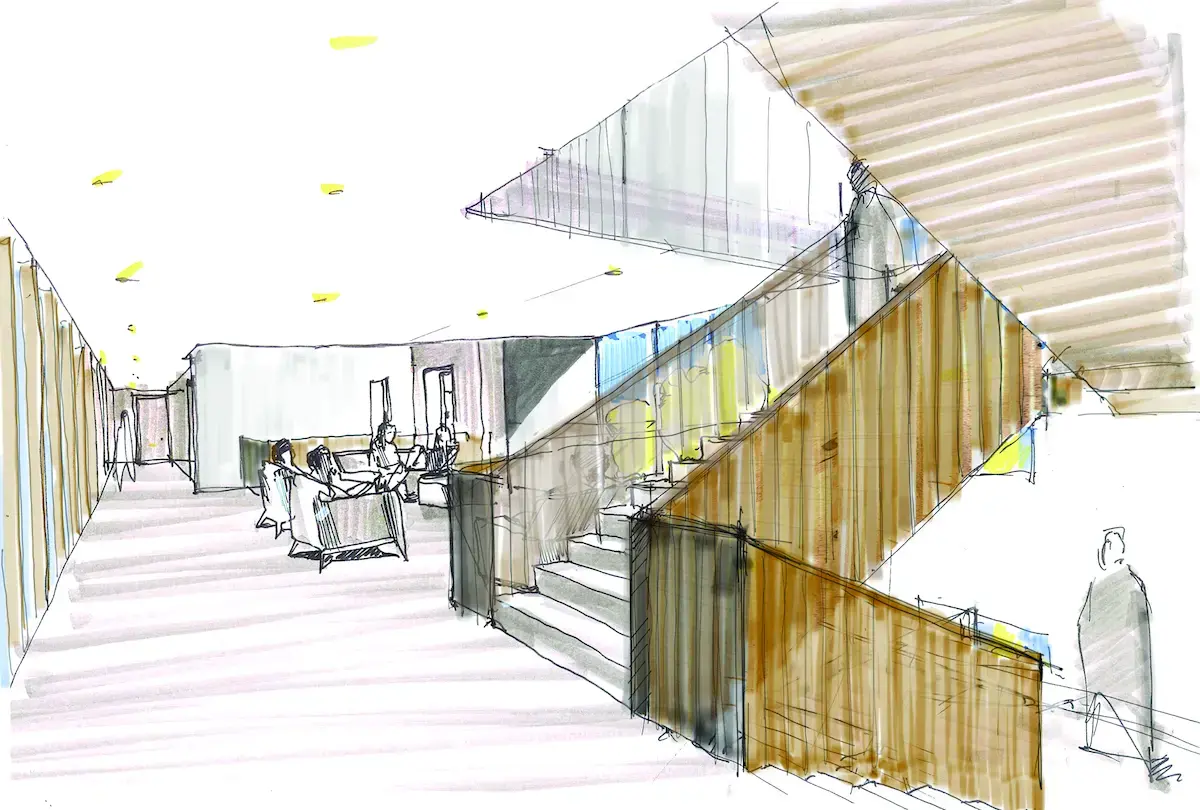

The northern entrance that had been a doorway but not an entrance is transforming to become a glassed-in portal to welcome people from that side of campus that has expanded so far beyond the original architects’ imaginings. There’s a planned terrace that wraps around the east side that will be an outdoor dining space to supplement the indoor dining rooms on the second floor.

“We’re making a building that rightly belongs at the geometric center of campus; one that is as open and accessible from the north, east, and west as it is from the south. A building in the round, that has many fronts, and one that programmatically serves as the embodiment of the Bennington experience: a place where learning happens as much in the more conventional space of the classroom as it does while communing over a meal, or socializing in the in-between spaces, says Martin Finio, co-lead architect for the project, along with Taryn Christoff, both of New York architecture firm Christoff: Finio.

Literature, language, and social science classes will be sited on the third floor, although the space won’t be “owned” by any discipline or entirely devoted to classrooms.

Spatially, the floor is shaped like the letter “H,” with the center bar of that letter representing Bennington’s original stage. What happens in this open-24-hours-a-day core space of the building is essentially up to Bennington students and will include peer education and peer learning spaces that are planned for, but informal.

I’ve always found it interesting about the campus that, even though it’s very symmetrical in its planning, there’s really no front door to any building. You sort of always enter diagonally on corners. You have to create your own path. Don Sherefkin

“We decided to take disparate areas of peer education and peer learning and centralize them. There are going to be peer tutors in writing and language and technology— students teaching, and learning from, each other. It’s the academic representation of peer learning. To have a space that physically embodies that is exciting,” says Dean of the Library Oceana Wilson. And Wilson’s is only one of the ambitions that will be realized here.

“It’s about collaborative space, weaving together the curricular and the co-curricular and giving that a home and a manifestation,” says Isabel Roche, Provost and Dean of the College.

Although disciplines such as philosophy, Spanish, or history don’t aim to produce physical objects in the same way as artistic disciplines or the sciences, some contemporary design principles in service of creative production are influencing planning for the spaces. For instance, the ideas animating Makerspaces—gathering tools (some of them interactive) and expertise together in loose arrangement to allow for adaptation, reconfiguration, and “temporary ownership” of a space to encourage collaboration and invention.

PEDAGOGY AND PLACE

Not every school has a physical manifestation of its philosophy. Don Sherefkin had a nonresidential college experience at The Cooper Union. Schlatter cannot recall a single space on the Dartmouth campus, where he was an undergrad, that brought everyone together. Schools do have a nominal center, a multifunctional hub of a building. Schlatter mentions Houston Hall at the University of Pennsylvania, where he attended graduate school, as an example. “A segment of the school used those facilities. Certain students gravitated toward using that building but it wasn’t the whole school,” he says. “That’s the big difference with Commons.”

Commons is designed (and thoughtfully un-designed) to be where all of what might possibly happen in a single place can—sharing a meal, eating alone, putting on a performance, watching one, taking classes, learning from friends, participating in a group meeting, having a chance encounter with a long-missed someone, studying, thinking in a flexible way.

But it’s not about being a flexible structure, a multi-use environment. Neither necessarily engenders community or experimentation—see the proliferation of co-working spaces in major cities across the country, which are open and adaptable but essentially empty. “Flexibility is wonderful, but neutrality is deadly,” says Sherefkin. “There’s nothing to work up against.”

What imbues a physical space with life is its context— the intention of its designers and its users.

“You have to imagine ways students and place interact,” says President Mariko Silver, a geographer by training. Silver sees an integral relationship between spatial environments and the theoretical space an inquiry opens. “Students are filling the space with their own work, the work of their peers and of their teams, their groups, their performance collective. Our entire institution and educational philosophy is based on the idea of students filling that space.”

“I think it is going to go a long way to create much more interaction between people from across the campus. Because there will be classrooms and dining and study spaces and multi-use spaces, it’s going to be a great place to see people you may not see on a day-to-day basis,” says Sherefkin.