Public Action Grantees | FWT 2023

Ade Byron | For my Field Work Term, I had the opportunity to intern at the Restorative Justice Center at UC Berkeley working under a Bennington alumni. I learned so much about implementing Restorative Justice both on college campuses and in the real world and returned to Bennington with a collection of resources and knowledge that benefit both my studies and the college as a whole. I worked with graduate students in repairing a number of harms that occurred on the UC Berkeley campus, brainstorming and implementing solutions, training both faculty and students, creating guides and resources, designing a website, and bringing all this back to Bennington. I learned a number of new skills, including time management, conflict resolution, mediation, active listening, and a number of others that have benefitted me both personally and professionally in great ways. In addition to the work at UC Berkeley, I had the opportunity to explore Berkeley and the Bay Area, this being my first time on the west coast. I hiked, went to museums, beaches, parks, on boats, experienced numerous different cultures, saw the Golden Gate Bridge and ate a lot of new and different foods. I had the chance to see several different ways Restorative Justice is implemented, something I haven’t experienced much in the northeast. I got to see it used in all levels of education, in the justice system, in law, in prisons, in communities, and in the workplace. I both attended trainings, and assisted in leading trainings. After having this experience, I came back to Bennington prepared to work with the RJ Collective in implementing an RJ Connect on our campus with a number of new tools and skills. I’m so grateful to have had this opportunity!

Kathleen Castro | For my Winter 2022 FWT, I was extremely fortunate to have been granted the Newman and Cox Public Action Fellowship. The Fellowship helped me fund and realize an ethnographic research that I designed based in San Juan, Puerto Rico during which I stayed in San Juan for a week and interviewed migrant Uber drivers and hotel workers. I then worked with my Independent Study advisor, Özge Savaş, on learning how to conduct a thematic analysis of the interviews. I translated each interview from Spanish to English, engaged in readings, coding, conversations and found many interesting themes throughout the interviews that included education, politics, acculturation, family and economy. I found the work to be gratifying and I feel I now have a solid foundation for my understanding of why people migrate to San Juan. There is no one reason. There are multiple well-thought out reasons for people both deciding to move to San Juan and working in the jobs that they do. They are extremely goal oriented. I submitted an abstract of this research as a Poster Presentation at the upcoming Society of the Psychological Study of Social Issues Conference (SPSSI) in Denver, Colorado which will take place June 25th to June 27th of this year. The submission was accepted and I will be traveling to Denver to present it then. In the meantime, regardless of my FWT being over, my work on this research is far from complete. I will continue analyzing and engaging with the themes of this research and begin work on my Poster Presentation. Since I am a transfer student and also a senior in my last semester of college ever, I feel especially thankful and grateful to have been given the opportunity to create my own research project on a community I truly care about and admire.

Anna Chuna Chugay | Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union in 1937 was a forced transfer of the whole population of Koreans (172,000 people) from far East Russia to the desert unoccupied territories of current Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. This deportation is viewed as an example of racist policy in the USSR and ethnic cleansing of the Russian-Korean diaspora, also known as Koryo-Saram. The generation of the deportation survivors did not witness rehabilitation after the Soviet Union collapsed, so both the ways of resilience and a forced silence have been passed to their children and grandchildren for decades. This research shows how Koryo-Saram, which is now scattered across the globe, found different ways of healing and restoring the cultural identity that has been thoroughly erased by the Soviet regime. Over the winter I continued with an extensive research of the Population Transfer of Koreans and also interviewed Koryo-Saram people. This historical event is not broadly studied, even though that was the first case of an ethnic cleansing in the USSR, and led to a series of deportations signed by Stalin (for example the deportation of the Crimean Tatars or Chechens). My initial goal is to contribute to bringing awareness and international recognition to the Koryo-Saram community. I want to make this information more accessible for younger generations of Koryo-Saram, who did not have a chance to hear about this part of their history from their family members. This research is an enormous step towards developing this idea, as it allowed me to collect general information, find declassified NKVD documents and census of the Korean population that was taken during the deportation, give voice to children of the survivors and hear the real history. The discussion is a radical and political action that this Koryo-Saram generation, myself included, takes in the given context of the current Russian stance, hence I am proud and grateful to do this work within the Public Action Fellowship in CAPA.

Malvika Dang | As a Newman and Cox Fellow in Public Action, I had the opportunity to work at NPR’s TED Radio Hour. During the short span of six weeks, I was able to further my interest in journalism and understand its unique position in public media. While I am primarily interested in video journalism, working at NPR elevated my sense of what it meant to produce – adapting to the needs and demands of the creative medium while not compromising on the quality of the content which feels like a universal or central component vital to the fields of video and audio journalism.

Although my team worked remotely from different parts of the country, I was able to shadow interviews, pitch episode ideas, draft questions, research guests, explore archives and shadow producers. I was captivated by the shared sense of responsibility for sculpting masterpieces, be it in the newsroom or programming. Edits for each program were finessed to their prime and fact-checked to ensure that the overall result was melodic to the ear. Given the nature of the show, working at the desk resisted monotony and sufficiently fed my curious and creative mind.

During the last week of my fellowship, I had the opportunity to work from the headquarters in D.C. I met with senior producers, supervisors, and creators across NPR’s various shows. I even had the chance to attend Tiny Desks! I got to share notes, ask questions, and source inspiration for potential projects.

This experience left me with a sense of community within the field of video production and journalism. I feel braced to embark upon the responsibility of producing my own documentary as I step into my senior year.

Malva Miranda | I spent this FWT next to the Misuahallí river, in the Ecuadorian door of the Amazon, getting to know the midwives of Amupakin, a Kichwa Health Center. I was training as a midwife as well as accompanying the daily work these mamas do, which includes making thread out of different plants to make their shigras (bags) and knitting them; finding wood, collecting plants to make medicine; cooking for all the people that spend the day in Amupakin; waving baskets, attending patients. As a midwife trainee, I was assisting prenatal and postpartum visits. The archimamas would use their hands as a unique method to find the position of the baby, and would “accommodate it” to the correct position which --equally as the practice of vertical birth-- prevent many c-sections (which are indiscriminately programmed by the public and private hospitals and subcenters).

I arrived with several doubts about the program (PIPKA) and left with incredible gratitude and respect for its creation: the pedagogy is deeply coherent with their culture. Even if I had precious workshops, the way the archimamas learned their profession back in the day, was by following their parents, aunts, and grandmas in their daily practice as healers and midwives; and thus, this was the most familiar way for them to share knowledge. This meant that knowledge was transmitted while doing the daily chores, and allowed for the development of a personal relationship between the students and the archimamas. Additionally, as part of their work, the mamas would take forward community visits in which they walked to more far away localities, knocking on doors and stopping people in the street to find out who was pregnant in each hamlet. This provided the students the opportunity to understand the realities of the women who would visit Amupakin later. The point of these new visits was to promote the fact that controls and births in the Health Centre were now free (made possible through the economic contribution of the trainees).

Words are not enough to explain how powerful this experience was. To see that the jungle provides all the medicine, all the nutritious food, the materials to make textiles, daily utensils (including the tools used in the whole birth process), and materials to build the houses. There was nothing needed from the ‘outside’ in their daily life and medicinal practice. In the context of indigenous knowledge being systematically erased and limited by the government and companies, this experience provided me with insight in what is the immense power that is being deprived of whole societies. The opportunity to healthier lives. The opportunity of abundance. The opportunity for better attention. The opportunity of respect. The opportunity for real and thorough alternatives to this system of dependence and impoverishment.

Aahir Mrittika | I interned at the Child Health Research Foundation to learn their software tool: Paratype. During the lab rotation through clinical microbiology lab, molecular biology lab, environmental surveillance lab, and genomics lab, I learned the process of sequencing and storing genetic data, starting from patients’ sample collection to Next Generation sequencing mechanisms. CHRF has been at the forefront of advocating for accessible healthcare and vaccines, to prevent endemic infections in children that continue to terrorize South Asia at large. Working with sincere young scientists with the radical dream of transforming public health has opened my eyes to what we can do when we believe in our work. I tested patient samples for presence of pathogenic bacteria and antibiotic resistance, extracted RNA from covid samples and carried out quantitative PCR, and analyzed raw reads of paratyphoid strains using Unicycler (genome assembly), ResFinder, and Paratype. This culminated in a final project of running raw data on my own and exploring the innerworkings of the newly released Paratype, that I presented to other student interns and the CHRF crowd! Paratype is a database of paratyphoid strains (causal agent of paratyphoid fever, the lesser known version of typhoid) by their spatial and periodic diversification in South Asia: a highly neglected pathogen in a highly neglected region. The theme of public action and vaccine advocacy was contextualized by real databases and a history of fighting to make vaccines state sponsored and available. Although challenging at times, it was rewarding and educational to observe so many dimensions of healthcare together.

Elizabeth Pollom | This past field work term, I worked for the Restorative Justice Center at UC Berkeley. Here, I helped put together manuals to be used for training sessions. During these training sessions, I was mainly a participant, though I helped plan, prepare for, and set up. I worked closely with Julie Shackford-Bradley, who currently runs the Restorative Justice Center. With her guidance, I learned several ways to benefit the Restorative Justice Collective at Bennington College. With this information, I was able to see the way that another college benefits from the use of restorative justice on campus, providing me with tips on how to implement it on our own campus. I have been working from the beginning of my time at Bennington to help establish a student-led group of individuals committed to using restorative justice on campus for community building and conflict resolution. Being at UC Berkeley, I was able to see how they started it, as well as how they kept people interested in continuing the work. I was also given the opportunity to hear about cases of conflict that they had been able to provide restorative resources into. This gave me an idea of how it could potentially work at Bennington. This amazing field work term also provided me with connections I would not have had otherwise. I was able to ask questions I previously did not have anyone to ask, such as the challenges other college students have faced in using restorative justice in a campus community. With this, I was given insight on how to avoid certain challenges, as well as efficient ways on how to handle them, if presented with the same.

Alyssa Pong 庞利艳 | Ambiguous Assemblages is an ongoing two-part project—thesis and documentary—centering the many connections that heterogeneous Southeast Asian communities share with one another. I was curious about how “cultures overlap, borrow from each other, and live together,” to quote Edward Said. With the support of the Newman and Cox Fellowship, I made my way home to Malaysia, and began to do just that.

In many ways, Malaysia is representative of this mix of identities; our artistic practices emerging from an intermingling of backgrounds. Unlike my parents, I didn’t grow up knowing this. Where wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) once told the Sanskrit epic, Ramayana, it now tells the Malay rendition, Hikayat Seri Rama. All-women Mak Yong troupes who once traversed the country sharing the dance-theatre tradition are now banned from doing so; the form also stripped of any allusions to Buddhism. The government’s hyperfixation on the homogeneity of ethnic and religious identity attempts to render the hybridity of art as invisible and, at times, illegitimate.

And yet, in meeting various practitioners and educators across the country, I witnessed the sheer resiliency of both art and the communities existing alongside them. With a camera in hand, I spoke to Odissi dancers who embodied a mesh of stories and philosophies; I listened to Malay folk music being passed down to the next generation. The project brought me to the east coast, to the “tax free zones” where Malaysia blurs into Thailand, and to the serene mosques built of Chinese characters inscribed in jade. Everywhere I looked there was evidence of this collapsing of cultures. It was a departure from what I thought I knew. But what became clear to me was the semangat–spirit–that bound each of these things. It is this connective tissue that I hope comes through in the scenes I documented and the people who persist regardless.

Image description: At the Malay Ethnographic Museum viewing a collection of 90 shadow puppets from the east coast state of Kelantan. Photo captured by the museum's curator, Mr. Mohamad Anis bin Abdul Samad.

Alisha Shrestha | “Nepali Feminist Movement: Personal and Political” was supported by Newman and Cox Public Action Fellowship. Using oral history, found images and footage, empty architectural enactments, and the public life of women, this project utilizes motion images to produce a hybrid documentary to explore the changes of woman rights and personal womanism in Nepal. The project is one of recovering and rewriting, and utilizes a feminist methodology of primary research that is garnered from women’s experiences. This rewriting of rhetorical practise of feminism in the Global South—a small developing country, Nepal required a deep personal reflections alongside a collage of listening, researching about the socio-economics of the country and mindful contemplation in regards to the lives of the women who lived during that period of time. The majority of the production was done during winter 2022/23 and the post production will be done for the senior work showing of Spring 2023.

Saira Shrestha | In August 2022, the police of Kathmandu Metropolitan City conducted an aggressive excavation and confiscation of goods from street vendors operating in various pedestrian designated areas in the valley. These street vendors, often referred to as local hustlers, set up pop-up shops in high foot-traffic areas around the city selling a vast range of products, including fresh fruits and vegetables, easy-to-make fast foods, cheaply sourced textiles from larger Chinese companies, fakes of designer goods, secondhand books, and oxidized jewelry, among others. However, complaints from locals and pedestrians have created a decade-long hostility between the vendors and the city police. According to the Street Vendor’s Traders Union, there are more than 45,000 street vendors in Kathmandu alone, making up 10 percent of the national economy. Therefore, ad hoc crackdowns and violent implementation of policies are not the solution.

During my FWT, I conducted independent research working with the Street Vendors Union and Satori Center for the Arts at the intersection of design, space, and policy. My interactions with the locals and street vendors allowed me to gain an in-depth understanding of the challenges they face and the potential solutions that could be adopted. One possible solution is to create a multi-use, multipurpose park that can also be used as commercial zones for street vendors during evenings. This would require a thorough understanding of the urban design of Kathmandu, the needs of street vendors, and the context in which they operate.The proposal would include architectural ideas, drawings, and a 3D model and I'm inspired to take this further as my Senior Project in Bennington College

Addressing the issue of street vendors in Kathmandu requires a comprehensive approach that takes into account the complex challenges of urban planning, the economics of public space, the working class, and policies. By providing a space for street vendors to operate legally and sustainably, we can create a better urban environment for city dwellers while also supporting the working class and the local economy.

Samuel De Sousa De Abreu | For my FWT I conducted an independent research on civil society and activism under current Maduro's Venezuela. The chavista government has become progressively more autocratic and the country is experiencing higher social inequalities in the recently dollarized economy after many consecutive years of economic recession. Thus, different social movements and civil groups have organized to demand the fulfillment of constitutional socio-economic Human Rights as well as minority rights. Asking for social and economic concessions to the regime instead of directly pushing for political change, as this latter approach has dramatically failed in previous years in the hands of brutal military repression from the government. Meanwhile, the political opposition seems to have lost the Venezuelan people's trust after failing to effectively bring political change as promised on multiple occasions, besides having been out of touch with more tangible issues that affect people’s daily lives. Therefore, numerous NGOs have emerged in recent years to fill the void left by an increasingly absent state and a weakened productive private sector. While activists continue to build organizational capacities that allow them to have more bargaining power in the exclusive decision making process. There are, however, various factors and apparent contradictions that hinder grassroots coalition building in this particular dictatorial context. Factors that were the focus of my research when interviewing influential activists, politicians and other civil society actors currently working towards a fairer and democratic Venezuela.

Stefanos Zogopoulos | I am a senior student studying Costume Design, Directing, and Theater Administration among other things. My work focuses on how tactile and physical forms can generate a narrative of their own. Exploring the relationship between textiles, and inter- and intra-personal relationships is what I take into consideration when I think of design.

For my last FWT, I was honored to receive the Newman and Cox Student Fellowship Grant. With the aid of this grant, I was able to pursue an internship with Transform 1012. Transform 1012 N. Main Street (T1012), is a Texas-based, non-profit coalition of 8 local arts, grassroots, and service organizations and groups. Their mission is to transform this monument to hate into a beacon of truth-telling, reconciliation, and liberation for the nation. The Fred Rouse Center for Arts and Community Healing – a reparative justice project – will honor the life and memory of Mr. Fred Rouse, a Black butcher who was lynched by a White mob in Fort Worth in 1921, by returning resources to the communities that were targeted for marginalization and violence by the Ku Klux Klan.

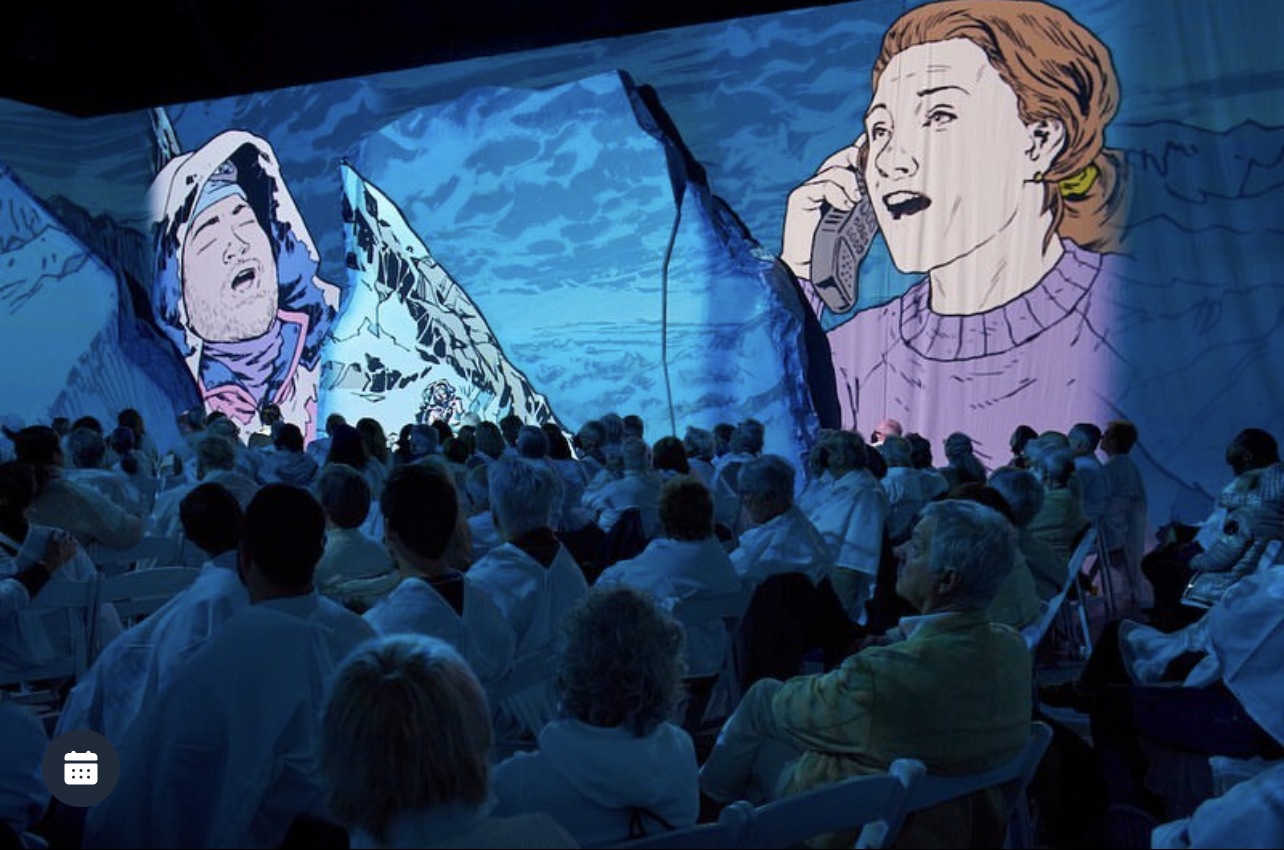

My second FWT was with Z Space Theater. Z Space empowers artistic risk, collaboration, and camaraderie amongst artists, the audience, and the community in the service of creating, developing, and presenting new work. During my time there, I was fortunate to assist with an Opera Parallele production called "Everest: An Immersive Experience" - A 360-degree visual space that places you in the center. Detailed Surround Sound audio of the frigid soundscapes of the tundra. Multiple-perspective projections allow you to be in the suburbs of New Zealand and the top of Everest at the same time. All in service to an epic story about triumph, family, and loss.